Tell me about the documentary, what does it tell?

Well, it’s a documentary in which I condense research on Buñuel that I’ve been doing for many, many years. I started in 1999, in the last century, when they wanted to create the Casa Buñuel in Calanda. So in all that time I have met a lot of people, who have later become friends, like Jean-Claude Carrière, like Juan Luis Buñuel, who have told me many anecdotes, many stories about Luis Buñuel. And it is with all this research and the memory of these conversations with these friends that I have concocted this new documentary entitled ‘Buñuel. A surrealist filmmaker’.

And I understand that the production was set in motion during the confinement by Covid-19, because somehow a lot of things I had thought about Luis Buñuel resurfaced.

Exactly. I was working on another project that I had to put on hold because of Covid, and I had given a lecture at the Cineteca Nacional de México with the title ‘Luis Buñuel. A surrealist in Mexico’. It was a success, full to overflowing, and many people urged me to make a documentary with all the material I had been showing. I said no, that a lecture is one thing and a documentary is another, that they have a totally different rhythm. And that’s where the project stayed until, locked up at home when we couldn’t go out, I set it as a challenge. I started working to prepare a script and that’s how it all began.

What was the research process like, preparing the materials? Because unpublished documents have also appeared.

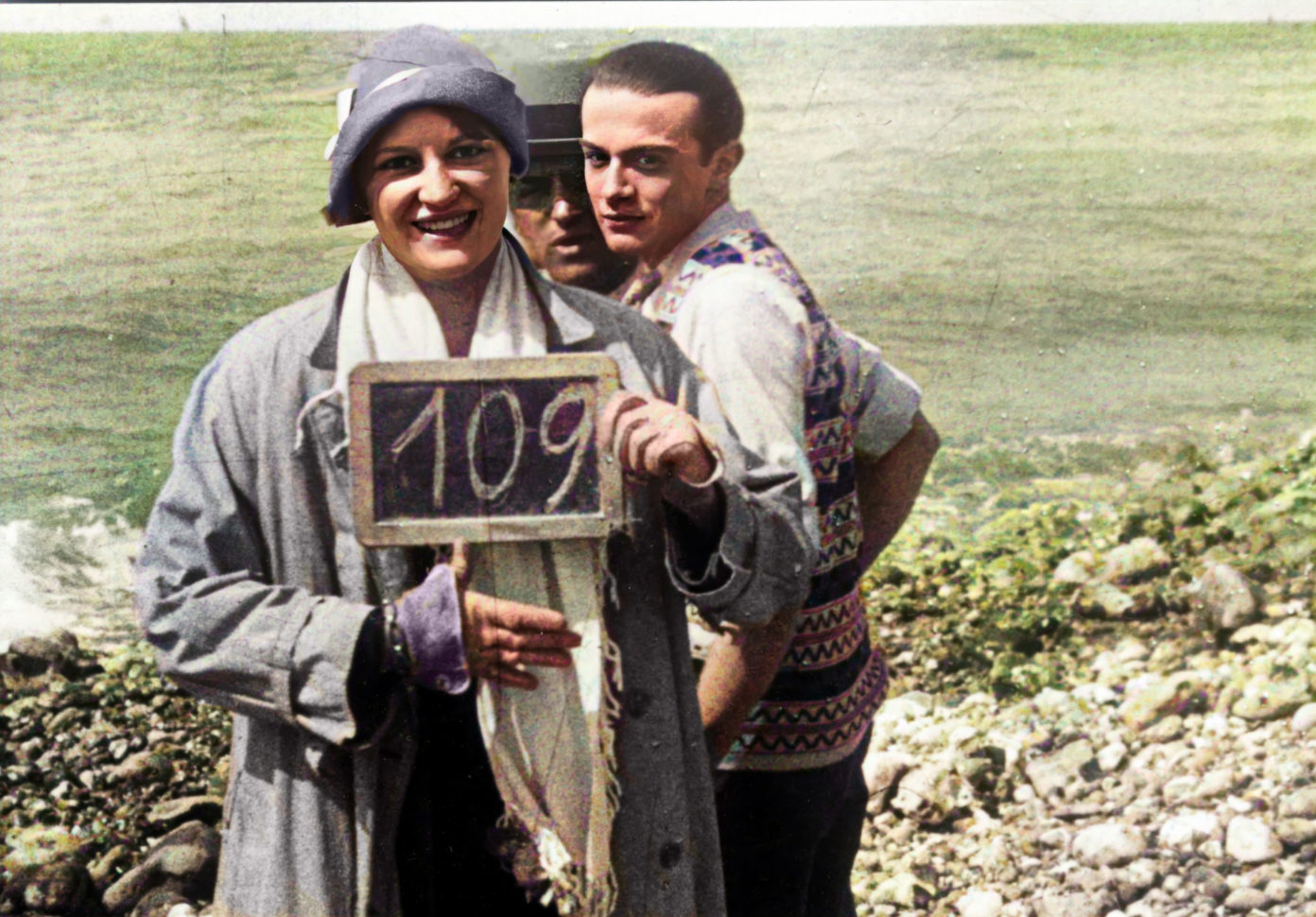

On the one hand, I have had the opportunity to access restored films that have not yet been seen publicly, for which I am very grateful to the Cineteca Nacional de México, the Filmoteca de la UNAM, the Filmoteca Española and the Filmoteca Francesa, which has even given me access to the discards from the filming of ‘La edad de oro’, totally unknown material.

Buñuel is an icon of Surrealism, and although at a certain point he stopped making explicitly surrealist films, such as ‘Un perro andaluz’ or ‘La edad de oro’, he never abandoned this movement.

Of course, Buñuel was a surrealist before he met the surrealists. He thinks that ‘An Andalusian Dog’ was signed before he joined the surrealist movement, writing the script with automatic writing processes with Salvador Dalí. And all this meant that when the surrealists saw the film they recognised it as theirs and immediately Buñuel and Dalí were admitted into the select surrealist group, led by André Breton.

And why do you think Luis Buñuel chose this way of expressing himself?

I think it comes from his childhood. One of the theses I work on in this documentary is the influence of his father and a republican doctor from Calanda. These two influences have not been studied very much to date, but I think they are very important to understand Buñuel’s formation.

And in fact, among the unpublished material, a series of stereoscopic photographs that Buñuel’s father took on glass plates have been rescued and we have worked with artificial intelligence to restore them and give them an impressive quality.

Tell me more about the influence of this doctor.

If we take into account that he was a staunch Republican, that he was anti-clerical and that he loved insects and had an encyclopaedia dedicated to them, there are already a few elements that have a lot to do with Buñuel.

You say that, with this documentary, you want to open Luis Buñuel’s art to a new generation of creators.

Of course, I think Buñuel’s work is still inspiring, it is still very rich. He is already a classic director within Surrealism, obviously, but also as a filmmaker. And his work is also closely linked to literature, but also to the world of art, as I highlight throughout the documentary. I think that all this adds a very, very great richness. And I’m sure that any creator, not just a filmmaker, a writer, a photographer, when they are confronted with Buñuel’s work, will discover that there are many things that will touch them, there are many elements that form part of the universe that Buñuel creates and that will capture you.

In addition, he has a way of making films or telling things that is still relevant today, that has many things that can engage with the art that is being made now.

I believe that yes, it is still very current. And there is also an enormous lesson that he can teach new creators because he was very humble. He had very little budget and had to make his films with very little money, so he would go himself with his camera to locate the exteriors. And that meant that he had his films in his head even before shooting and that the filming was very fluid and economical. Nowadays many people look for a great script to make a huge film with a gigantic budget and great actors and actresses, but not Buñuel, Buñuel was capable, with a very elaborate script, of making films that form part of the history of art and cinema in capital letters.

They are also films that offer many readings. He brought very critical and profound themes to a majority of the public, who found films that could be seen in different ways.

Exactly, and also made with enormous freedom. I’m surprised by the freedom in Buñuel’s films, and I think that these films would be unthinkable now because of economic censorship, public pressure… these films could not be made because they would be frowned upon.

Tell me now about the route your film has taken. You’ve been to the Cannes and San Sebastian festivals, what was the experience like?

For me, premiering the film at the Cannes festival is an incredible success, because we are talking about the most important festival in the world, and also to do it in the Buñuel hall of the Cannes festival… I think there is no other place in the universe better to premiere this documentary film.

And it was also chosen to open the first edition of the Saraqusta Film Festival, in Zaragoza.

Exactly, after its participation in Made in Spain, a section that brings together the best of Spanish cinema of the year, at the San Sebastian Festival, it has opened the Saraqusta Film Festival, a historical film festival. And it is also going to be screened at the Spanish film festival at the Seminci in Valladolid, and also in Mexico, in Italy, back to France… And now I’m on my way to Madrid because the film is closing the Mestizolab, a Spain-Mexico co-production forum.

A journey that would be very special for any director, but I imagine even more so for you, who are from Calanda and have such a love for the figure of Luis Buñuel.

Of course, but the truth is that I have to confess that all the films I have made have had a great international tour and a great diffusion in the international press, sometimes, I have to confess, even more than in Aragon.

In this sense, do you think Buñuel is sufficiently vindicated here in Aragon? Because in places like Mexico he is an institution.

I think much more so in Mexico than in Aragon. And it hurts me, because I myself created the Buñuel Calanda Centre, I have directed it for many years and I have given it international projection precisely to vindicate the figure of Buñuel and his relationship with Aragon. But these are projects that have to be long-term and I think that, modestly, with this documentary I am also going to contribute to the dissemination of Buñuel and to this vindication of the Aragonese Buñuel, because the whole first part of the documentary has a lot to do with Aragon, and the end of the documentary, too.

I’m curious, because we always say, and it seems like a cliché, that Buñuel had Calanda and Aragon in him, but how does someone from Calanda like you perceive this?

Well, for example, in the shooting of the film Nazarín. When I was doing research I discovered a shoebox full of photographs in the Filmoteca Española and I came to the conclusion that Buñuel himself had taken them looking for the locations of his Mexican films. And of all of them, the one I had the most photos of was precisely Nazarín, because it is a film that is shot in many places. So I made a documentary about that film, using those photographs, looking for those places today. I found them all and I felt that Buñuel had chosen precisely those places because they had something to do, a secret, nostalgic link with his homeland: the dirt streets, the adobe walls, the silence… many elements that have to do with that deep Aragon that Buñuel knew.

You spoke earlier about the relationship between Buñuel and Goya. We are precisely celebrating the 275th anniversary of the birth of the painter, who is very closely connected to Luis Buñuel.

Yes, and it is also reflected in the documentary, with a joke that Buñuel made when he was at the Residencia de Estudiantes: he put up a poster for a guided tour of the Prado Museum as if he were a specialist, and many American teachers signed up for this visit, in which Buñuel made it all up and told them lies about Goya. It is an amusing anecdote, but it shows Buñuel’s great knowledge of the Prado Museum and its links with art. A secret connection, but one that is highlighted in the documentary.

You have done a lot of research on Buñuel, you have dedicated almost your whole life to his figure… are there still things left to discover about him?

Of course there are. This is a documentary of opinion, so to speak, subjective, made with the fruit of my research, my contacts, my conversations, my memories and the things I have found along the way over all these years. But elements continue to be found and anyone who starts to investigate will find other elements and can give another approach. I have focused this documentary, for example, on the figure of Buñuel and his links with Surrealism, but also closing a circle with the first documentary I made with Gaizka Urresti, which was a journey to the places where Buñuel lived, accompanied by Jean-Claude Carrière and Juan Luis Buñuel.

For example, when I made the film ‘Tras Nazarín’, about Buñuel’s film ‘Nazarín’, many people told me that you can make a documentary about every Buñuel film. You can make a documentary about ‘Los olvidados’, ‘Viridiana’, ‘El ángel exterminador’… there are many Buñuel films to which a documentary can be dedicated, and I leave the door open for future researchers.